The Macedonian conservative

What does it mean to be a conservative? Where does the tradition of being a conservative come from? What does it mean to be a Macedonian conservative? Without getting too deep in the weeds on the various strains of conservatism and conservative thinking, let’s start with the basics: being a conservative depends on what you want to conserve.

For instance, as an American conservative, I want to conserve the founding of my country and the founding principles set up by the Founding Fathers, and the framework (our Constitution) that governs our country. Across the Atlantic, our British conservative friends want to conserve something slightly different. For them, it is their constitution (which is not a written document), their history and heroes, and much more.

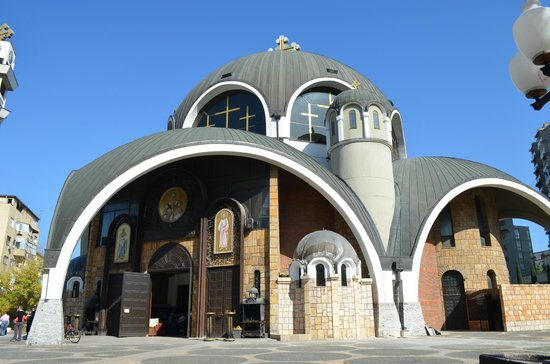

And for Macedonians? What does a Macedonian conservative want to conserve? As a long-time admirer of Macedonia and the Macedonian people and as one who has spent nearly a quarter of a century with Macedonia (including having lived and worked there for much of that time), I would submit that being a Macedonian conservative means wanting to conserve the Macedonian nation or people, wherever they live (and therefore the Macedonian identity), the entity that is Republic of Macedonia, as well as the unique things that make Macedonia and Macedonians just that – the language, history, heritage, culture, and faith, and in Macedonia’s case, the Macedonian Orthodox Church (there is much to discuss on this last issue which I will address in a future column).

Now, having distinguished the Macedonian conservative from their American or British conservative cousins, there are some attributes which are universal to all conservatives no matter where they live and no matter what their ethnicity or nationality happens to be. In this column, I want to address one of those, briefly; in future columns, I hope to expand on those, individually.

Having read and studied and listened to writers and thinkers, from Irish-Anglo writer and member of the English parliament Edmund Burke (1729-1797), who is largely credited as the founding father of conservatism, to the writers and thinkers of today, I have come to the conclusion that the first and foremost core tenant of conservativism is gratitude. Being grateful may seem like a strange way to begin an introduction to conservatism but when you really stop to consider it, it will hopefully become abundantly clear as to why gratitude is the bedrock of conservatism.

Think about it. When you are thankful for what you have, you tend to want to protect it and conserve it because you cherish it. One of today’s writers and thinkers who has greatly influenced me in my own journey of understanding conservatism is Yuval Levin, an American writer and vice president of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C. In remarks delivered to the Bradley Foundation in 2013, Levin noted “To my mind, conservatism is gratitude. Conservatives tend to begin from gratitude for what is good and what works in our society and then strive to build on it, while liberals tend to begin from outrage at what is bad and broken and seek to uproot it.”

He continues noting that “Conservatives often begin from gratitude because we start from modest expectations of human affairs—we know that people are imperfect, and fallen, and weak; that human knowledge and power are not all they’re cracked up to be; and we’re enormously impressed by the institutions that have managed to make something great of this imperfect raw material. So we want to build on them because we don’t imagine we could do better starting from scratch.”

He then compares that with our friends on the Left, writing “Liberals often begin from outrage because they have much higher expectations—maybe even utopian expectations—about the perfectibility of human things and the potential of human knowledge and power. They’re often willing to ignore tradition and to push aside institutions that channel generations of wisdom because they think we can do better on our own.”

In a separate but related essay, he notes that “The sense of man’s fallen nature often leaves conservatives with low expectations. But it is precisely because of those low expectations that we tend to be far more thankful for success in society than we are outraged by failure.” Comparing that attitude of gratitude with our friends on the Left, he writes that “Progressives have much higher expectations. They are more open to the possibility of the perfectibility of man, and they tend to think they have a formula for it, so the persistence of failure infuriates them. When conservatives are outraged, it is generally at seeing something valuable lost; progressives are more commonly outraged at the obduracy of the status quo.” You might notice a certain theme in his writing: conservatives do not believe in the perfectibility of mankind; our friends on the Left tend to believe that mankind can be made perfect which involves state power.

And then his beautiful summary: “An appreciation of and a gratitude for what works in society, and an inclination to address our failures by building on what works rather than starting over, give conservatives a high regard for long-standing social institutions—those that have been valued by generations of people dealing with the same kinds of basic human problems we now face. It is a key reason why conservatives are traditionalists, inclined to be protective of established ways.”

The ironic thing is that the opposite of gratitude is not necessarily ingratitude; it is resentment and entitlement. When you start taking these things for granted, you are less likely to defend them and they then become susceptible to corruption and decay. And then envy and greed set in and then resentment and entitlement.

So, how does this relate to the Macedonian conservative? To my mind, the Macedonian conservative is a man or woman who is grateful for the fact that an independent Macedonia exists – as and only as Macedonia – and not just exists, but was achieved in the first place after centuries of striving. The Macedonian conservative is thankful for the traditions and things that make Macedonia unique. The Macedonian conservative is indebted to those Macedonian men and women who came before and sacrificed for Macedonia. The Macedonian conservative has gratitude for the culture, language, history, and heritage of Macedonia. And in all of these things, the Macedonian conservative wants to hold on to these things and cherish them because they are worthy of praise and protection.

In my next column, I will list some of the additional core tenets of conservatism and will then expand on them, one by one in future columns.

0 Comments