There is wisdom in the old ways and tradition

In my last column I made the distinction between conservatives from different countries and backgrounds, arguing that being an American conservative, a British conservative, or a Macedonian conservative depends on what you want to conserve. I made the case that Macedonian conservatives want to conserve Macedonia, and all that makes Macedonia and what it is unique. I then noted that all conservatives, no matter what their country or background, all share some attributes which are universal to conservatives no matter where they live and discussed one of them, gratitude, and how gratitude applies to the Macedonian conservative woman or man.

In this column, I want to address another one of those attributes: wisdom in the old ways and tradition.

Canadian clinical psychologist and author Dr. Jordan B. Peterson writes “The wisdom of the past was hard-earned, and your dead ancestors may have something useful to tell you.”

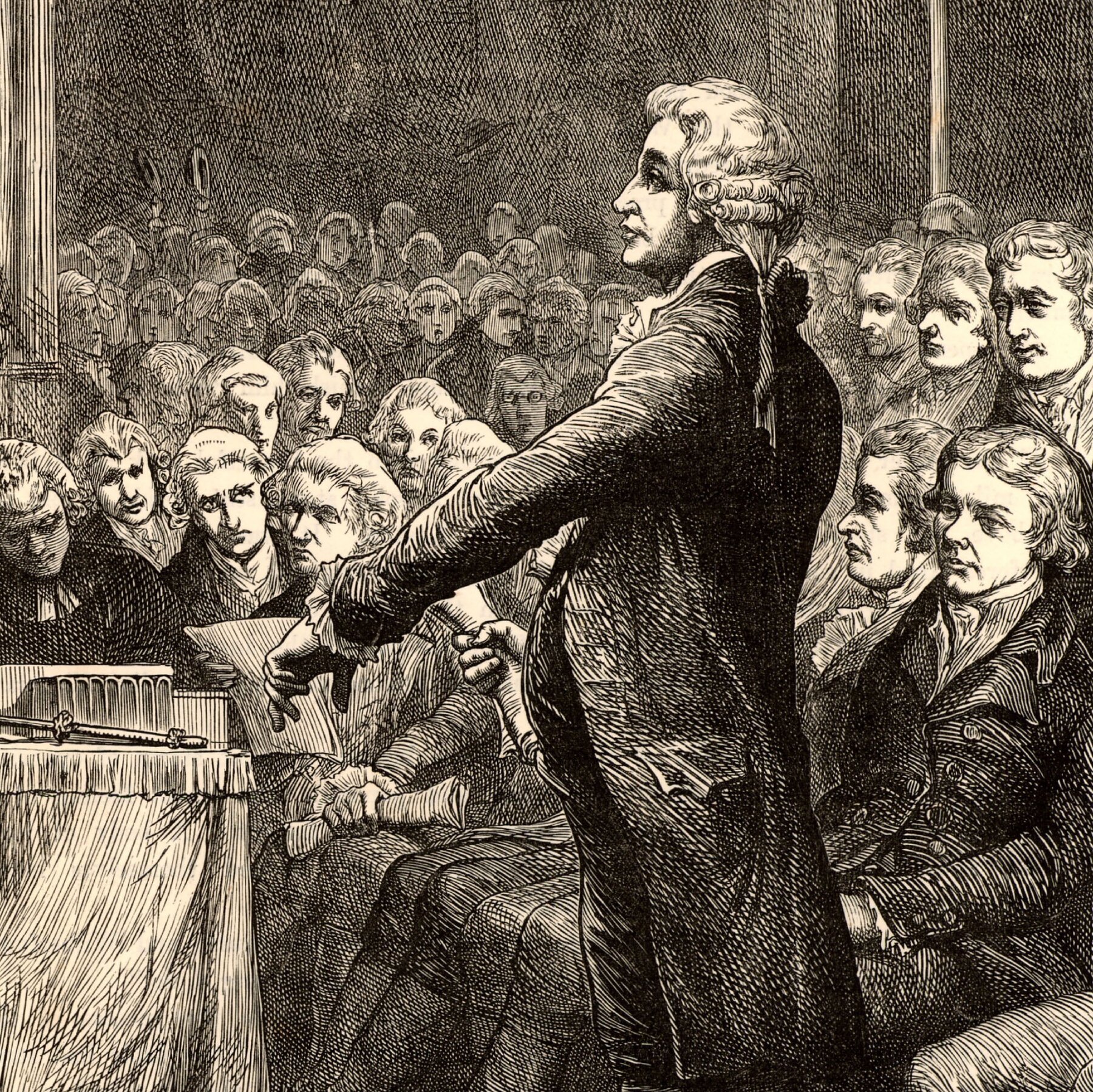

There are too many people these days who are willing to quickly discard the wisdom of the past, tradition, and the teachings and thoughts of “old dead white men” to use but one phrase popular today among some groups of people. But is that wisdom, which is found in the past, in tradition, and the teaching and thoughts of men – and women – something to be discarded, or is it something to be learned from? Can we garner and gather wisdom from the past? Is there something past generations can teach us? Anglo-Irish statesman and author Edmund Burke (1729-1797) believed so and wrote “Society is indeed a contract…As the ends of such a partnership cannot be obtained in many generations, it becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are yet to be born. Each contract of each particular state is but a clause in the great primeval contract of eternal society.”

English author, philosopher, and lay theologian G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936) had something to say about this as well, and, writing about democracy, tells us that “I have never been able to understand where people got the idea that democracy was in some way opposed to tradition. It is obvious that tradition is only democracy extended through time….Tradition may be defined as an extension of the franchise” [i.e. the right to vote]. Riffing on Burke he then writes “Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about. All democrats object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth; tradition objects to their being disqualified by the accident of death.”

Another thinker and philosopher, economist Friedrich von Hayek (1899-1992) makes a somewhat frightening point in “The Fatal Conceit,” writing “Virtually all of the benefits of civilization, and indeed our very existence, rest, I believe, on our continuing willingness to shoulder the burden of tradition. These benefits in no way ‘justify’ the burden. But the alternative is poverty and famine.” Or, as modern-day author Jonah Goldberg puts it, “Among the greatest benefits of old institutions is that they are old….Chopping them down with the aim of building a perfect society is the perfect recipe for destroying a good society. Because when you destroy existing cultural habitats, you do not instantly convert the people who live in them to your worldview. You radicalize them.”

While some leaders today in the West (and many of their followers) believe that they must “fundamentally change” their countries, change, just for the sake of it, is not always a good thing. Author and thinker Russell Kirk (1918-1994) suggests caution writing “Hasty innovation may be a devouring conflagration, rather than a torch of progress.” How all too often have we moderns observed this.

To all of this emphasis on tradition and the past we must add one vital ingredient: that of memory. The only way to reflect upon the past is to remember the past. That’s one reason why

George Orwell (1903-1950) wrote “The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history” while Russian dissident, author, and Nobel Prize in Literature winner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008) asserted “To destroy a people, you must first sever their roots.” And Milan Kundera (1929- ), in “The Book of Laughter and Forgetting”told us “The first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history…. Before long the nation will begin to forget what it is and what it was.”

So how does all of this apply to the Macedonian conservative? To my mind, the Macedonian conservative understands that you only get to keep Macedonia as a place, as an ideal, and as a culture (and everything that goes with it, including language) as long as you pass all of that down from generation to generation, just as it was passed on to those currently living. Think about it: reading this now, as a Macedonian, perhaps reading the Macedonian language version of this, you are a Macedonian, with a Macedonian consciousness and a memory of Macedonia, its history, culture and much more, because it was maintained and passed down to you by Macedonians who went before you, whether your parents, grandparents, more distant ancestors, or, perhaps, simply Macedonians whose names you will never know, who did the hard work of carrying Hayek’s “burden of tradition” and giving it to you.

The Macedonian conservative understands what Burke wrote: that your ancestors built something of great value through no contribution of your own which has been passed on to you today; therefore, your ancestors get a vote, in a manner of speaking, in whether or not you keep it. And the Macedonian conservative understands the importance of memory of that past, and that there is wisdom in that past, and that it is vital to keep that memory alive in culture, in education, in society, and more. Therefore, the Macedonian conservative wants to keep that memory alive to pass on to his or her children, grandchildren, and to “those who are yet to be born.”

In my next column, I will continue with this pattern of introducing and expounding on the different attributes of a conservative.

0 Comments